By Aymann Ismail

Around the city, many Black residents had a grim prediction for the outcome of the George Floyd case — but also some hope.

In Minneapolis, few can get anywhere near the Hennepin County District Court. It looks more like a barracks than a courthouse now. The building, where opening arguments begin on Monday for Derek Chauvin’s trial in the death of George Floyd, has been surrounded by military-grade barbed wire and fencing, and it’s guarded by National Guard soldiers scattered across the perimeter. Dozens of camera crews are positioned outside. Recently, as jury selection in the case began, there was an eerie quiet all around. People on both sides of the barricades stared at one another warily.

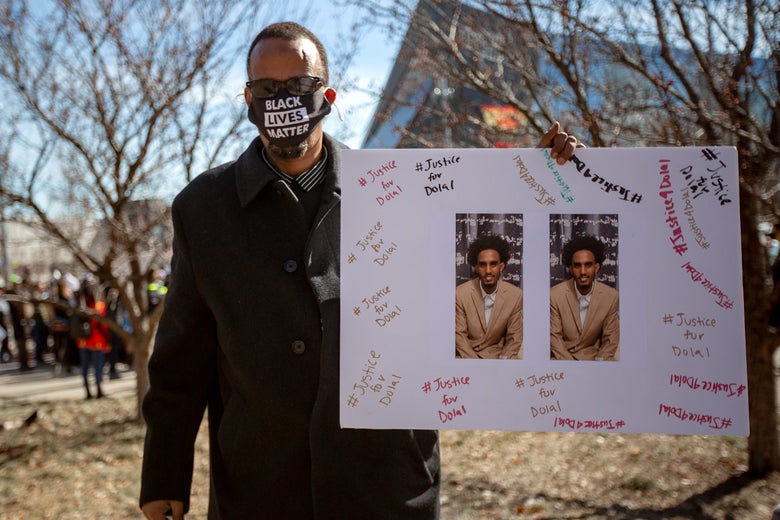

The only sounds in the area came from the occasional light rail and, on that day, the distant howls of about 300 protesters who marched nearby, followed by dozens of photographers and journalists. I followed the echoes of people chanting “Do the right thing!” to find them. Local organizer Toussaint Morrison was at the helm. “Let me tell you something about this building right here. It is undoubtedly going to affect every single Black youth in this state,” he said when they made it to the court. “What’s on trial is the value of a Black man’s life, and I don’t need the Hennepin County government to let me know if I’m valuable or not. The verdict can go either way.”

Morrison wasn’t the only one who seemed to be girding himself for the eventual verdict. As I spoke to Black residents around Minneapolis, they all had one prediction. “He ain’t going nowhere,” one man, Jaleel, told me about Derek Chauvin. “And I hate to say this in front of all these people out here protesting, but they’re not going to get him.”

Jaleel, who asked not to use his last name, was born in Minneapolis and has never lived anywhere else. (“It’s not a bad place. It’s a good place to live. It might get cold as shit, but it’s a good place to live,” he said.) He said he knew George Floyd well — and he can’t convince himself that Chauvin will be held responsible for Floyd’s death. He’s especially worried about what could happen in that event. “They’re going to find some way to get a hung jury, and they’re going to tear this mother up again,” he said.

Nearby, Katina, who stood with fellow public school teachers behind a banner for the Minneapolis Federation of Teachers, told me she’s not especially politically active, but came to the rally to set an example for her students. “We want to make sure that they keep hope in their mind. And that maybe justice just might be served, possibly?” She didn’t sound so sure herself. When I asked the outcome she was expecting at the trial, she gave me a careful look and said, “Just having hope is a good thing.”

Like many other teachers across the country, Katina said she worries about the mental health of her students, but is especially worried for kids in Minneapolis, who are experiencing “compounded stress” due to the trial. She’s lowered her expectations for her students’ ability to stick to the curriculum virtually and is hopeful that a year of protests like this one is teaching them in another way. “Even if they’re not learning English or social studies, they’re learning the history of America, and watching things change,” she said.

Inside the Hennepin County court, he told me he noticed something peculiar. “I was there in the media room watching the trial. One of the things that I noticed is that the prosecutor, the prosecutor attorney, and the defense attorney share similar concerns,” he said. “They want to impress upon people that the system works. They want people to accept the reality of the system, that a person isn’t guilty until the system says he’s guilty. You can see him commit a crime, but there’s a separate set of rules here. We also know that that’s not true. When you talk to Black people, that only holds true for wealthy people and the police.”At George Floyd Square that week, locals mourned the death of another man who was shot only steps from where Floyd died. Tommy McBrayer, a community organizer, was resigned when we spoke. “It’s tragic. I’m still feeling that trauma in my body. It’s been a roller coaster, mentally and physically,” he said of the past nine months, adding that the death of his friend recently and Floyd’s death are intrinsically tied. “I think Black folks will never get justice. We’re living in a white America where nothing has ever been justified. Even if you think I’m wrong, the proof is everywhere. We’re still only three-fifths of a person.” I asked if he worried about the trial’s outcome. “You can only control so much,” he said. “Of course I worry.” But if there is another uprising, he said he still felt conflicted about the last one: “I don’t think we got anything out of it, because we were just messing up our own neighborhood, but doing nothing is easier. It’s not necessarily better.”

Carmen Means, another local organizer, told me she’s also expecting a “not guilty” verdict, but she’s thinking of the trial and verdict from another perspective. “I’m a mama, so the justice isn’t just for me. I have sons, and when you have children, your stance has to be different. Will it be heartbreaking beyond belief? Absolutely. But I have to remain hopeful.” Even so, she said she couldn’t say for sure how she’ll react. “I’ve never watched that tape in its entirety, the 8 minutes, 46 seconds — I couldn’t, and I can’t. But secondhand trauma is real, and I don’t know how my body will respond. And whatever way my body responds, I’ll give it space for that.”